Maybe you’ve been hearing about something called Georgia FLOST—and no, it’s not a new step in your bedtime routine.

The Floating Local Option Sales Tax is a new tool that counties and municipalities can adopt to deliver property tax relief. FLOST allows communities to levy a 1% countywide sales tax (in addition to existing local option sales taxes) for up to five years, with the option to renew. Revenue is shared through an intergovernmental agreement, and by law, FLOST proceeds must be used exclusively to reduce property taxes.

With the passage of HB 581 in April 2024, Georgia updated its statewide homestead exemption to limit inflationary increases in assessed values. The same legislation also authorized local governments to adopt FLOST, giving communities a new way to support essential services while easing long-term property tax pressure.

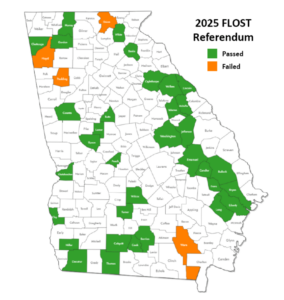

Growing Momentum Across Georgia

Interest in Georgia FLOST has spread quickly. In the most recent election cycle:

- 34 counties statewide have now adopted FLOST

- 32 out of 36 November referendums passed

- Approving counties saw an average 71% “yes” vote

These numbers reflect strong voter appetite for predictable, tangible property tax relief.

Eligibility: Coordination Isn’t Optional

One of the most important—and often overlooked—features of Georgia FLOST is how interdependent eligibility is across jurisdictions.

Here’s the short version:

- If any city that levies a property tax opts out, the entire county becomes ineligible for FLOST.

- If a city without a property tax opts out, there is no effect on eligibility.

- If a county opts out, all municipalities within it become ineligible unless the county has another qualifying homestead exemption.

- Jurisdictions with alternate eligible homestead exemptions can opt out without harming countywide eligibility.

The message is simple: eligibility rules make coordination essential. You can learn more from communities, such as Statesboro and Henry County, that have already published clear public information pages, explaining their FLOST timelines and eligibility steps.

Why Georgia FLOST Matters for Communities

For counties with a strong retail base, one penny can go surprisingly far.

1. FLOST strengthens competitiveness

A steady stream of sales tax–based revenue can help counties lower property taxes for homeowners and businesses: making the community more competitive with neighboring jurisdictions. Lower millage can influence where companies expand, where families buy homes, and where developers place long-term investment.

2. FLOST shifts part of the burden off property owners

Visitors, commuters, and shoppers contribute to the sales tax, reducing reliance on residential and commercial property owners alone.

3. FLOST creates opportunities—but only with preparation

Communities seeing new investment should immediately revisit foundational questions:

- Is your zoning code up to date?

- Do your land use policies support the growth you want to attract?

- Does your long-term strategy align with the benefits delivered by lower property tax pressures?

This moment isn’t just about revenue—it’s about using FLOST to support the kind of community you want to build.

How CEDR Helps Local Governments Navigate FLOST

FLOST opens the door to new possibilities, but communities need informed guidance to make the most of it. Our team supports municipalities and counties with:

- Fiscal analysis & long-term modeling: Assessing potential revenues, projected millage rollbacks, and multi-year implications

- Zoning & land use alignment: Updating codes to match growth opportunities fueled by increased competitiveness.

- Strategic planning: Connecting FLOST revenue patterns with broader economic development goals.

- Communication support: Helping leaders explain benefits clearly to residents, boards, and stakeholders.

If your county is considering—or has recently adopted—a FLOST, this is the ideal moment to align planning efforts with the opportunities ahead.

Let’s make sure your community is ready to maximize the benefits.

Get in Touch with our Economic Insights Team